What did people do with disabilities of the Great Patriotic War in the USSR?

Here you will learn about how the Soviet state dealt with Soviet citizens mutilated during the Second World War. Including soldiers and officers, who undermined their health while defending the country and the totalitarian Soviet regime.

In the Soviet Union, at the time of the end of the war and for many decades after, there was no single program of assistance to war disabled — as you already understood, there was not even such a simple thing as a wheelchair. People with disabilities rarely could even find a job or help them in any way, they either had a very small pension, or (more often) did not have it at all — and those disabled people who did not have compassionate relatives were forced to beg on the streets, quietly asking for alms near shops and squares.

Instead of helping these people, socializing them and giving them the opportunity to feel needed, the Soviet government decided to remove them from the city out of sight. At that time, the broad avenues with high houses were built, and the war disabled, in the opinion of the Soviet authorities, «spoiled the view of socialist happiness.» Simple Soviet pioneers should not see and know the truth about the war — it will be told them by youthful policemen strolling through schools with «front-line bikes». We will remove away the veterans and heroes who gave their health to the war — so as not to spoil our view here Soviet paradise.

The first mass deportation of war disabled outside the city limits occurred in 1949 and was timed to the 70th anniversary of Stalin. Everything was done according to the precepts of the greatest helmsman — «no man — no problem». Disabled on homemade strollers were caught on the streets, and if it turned out that the person has no relatives — then he was expelled outside the city limits. Nobody specifically asked people with disabilities if they want to go somewhere, their passports and soldiers’ books were taken away and, in fact, they transferred to the status of prisoners.

The deportation of 1949 is only one of the most famous. In fact, people with disabilities were caught and expelled from 1946, in the Stalin years and successfully continued under Khrushchev — armless and legless «beggars» were caught on the railway in his time.

The boarding houses to which people with disabilities were sent were under the Ministry of Internal Affairs and most closely resembled the structures of the Gulag (famous Soviet concentration camps) — the institutions themselves were closed, there were no rehabilitation programs, no proper care for people with disabilities, and the meager content was stolen by staff. In a word, the only task of these institutions was to promptly send the «unnecessary people» to the grave.

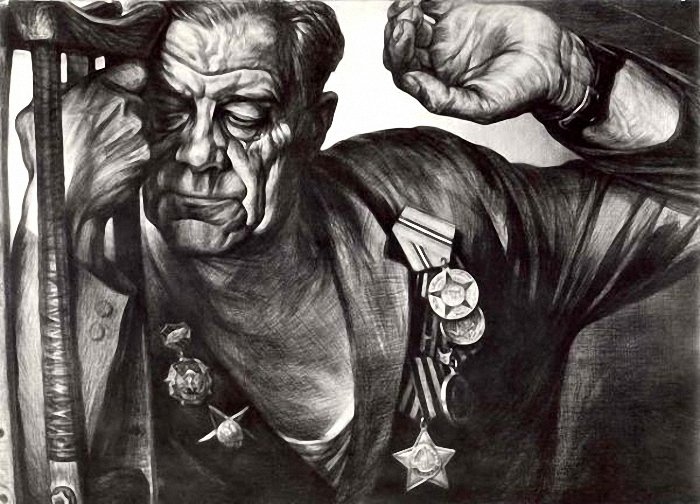

One of the deportation places of «unnecessary people» was the island of Valaam. In general, there were dozens of such places, but Balaam was perhaps one of the most famous — especially because artists came to the people who were sent there and were able to make drawings — so that at least some memory of them remained.

After the arrival on the Valaam, people “caught” on the streets were deprived of passports, soldier’s books and all other documents, including award documents. Disabled people were settled down in old monastic buildings that were practically uninhabitable — in many buildings, there were no roofs, no electricity, no doctors and nurses. Many war veterans who had survived the terrible war died in the first months of their stay on the island.

Yeugeny Kuznetsov wrote such touching and bitter lines in the book «Valaam Notebook»:

“The country of the Soviets punished its disabled winners for their injuries, for the loss of their families, shelter, and their nests, ruined by the war. The country punishing them with poverty, loneliness, hopelessness. Everyone who came to Valaam instantly realized: That is all! Next is a dead end. Further will be the silence in the unknown grave in an abandoned monastery cemetery.

Reader! My dear reader! Do we understand today the measure of unlimited despair over the grief that has invaded these people at the moment when they set foot on this earth? In prison, in a terrible gulag camp, the prisoner always has hope in there to get out, to find freedom, a different, less bitter life, but there was no outcome. The only way is to the grave.

I saw this entire close for many years in a row. It is very hard to describe. Especially when their faces, eyes, hands, their indescribable smiles, smiles of creatures appear in my mind’s gaze, as if in something forever guilty as if asking for forgiveness. No, it is impossible to describe. It is also impossible, probably because the memory of all this simply stops the heart, takes a breath, and an impossible confusion arises in our thoughts, some kind of clot of pain! Excuse me…»

Such, indeed, it was.